Vita Sackville-West

| Vita Sackville-West | |

|---|---|

By Philip de László |

|

| Born | 9 March 1892 Knole House, Kent, England |

| Died | 2 June 1962 (aged 70) |

| Occupation | novelist, poet |

| Nationality | English |

| Period | 1917 - 1960 |

| Spouse(s) | Harold Nicolson (m. 1913–1962) |

Victoria Mary Sackville-West, The Hon Lady Nicolson, CH (9 March 1892 – 2 June 1962), best known as Vita Sackville-West, was an English author and poet. Her long narrative poem, The Land, won the Hawthornden Prize in 1927. She won it again, becoming the only writer to do so, in 1933 with her Collected Poems. She helped create her own gardens in Sissinghurst, Kent, which provide the backdrop to Sissinghurst Castle. She was famous for her exuberant aristocratic life, her strong marriage, and her passionate affair with novelist Virginia Woolf.

Contents |

Early life

Sackville-West was born at Knole House in Sevenoaks Kent; the then laws of primogeniture prevented her from inheriting the estate on the death of her father, and Knole and the title instead passed to her uncle Charles (1870–1962). The loss of Knole would affect her for the rest of her life: of the signing in 1947 of documents reliquishing any claim on the property, part of its transition to the National Trust, she wrote that "the signing... nearly broke my heart, putting my signature to what I regarded as a betrayal of all the tradition of my ancestors and the house I loved." She was the daughter of Lionel Edward Sackville-West, 3rd Baron Sackville and his wife Victoria Sackville-West. The surname Sackville-West resulted from the marriage of Vita's great-grandmother Lady Elizabeth Sackville (1796–1870) to George Sackville-West, 5th Earl De La Warr.

Christened "Victoria Mary Sackville-West", she was known as "Vita" throughout her life. She was a descendant of Thomas Sackville, contributor to Gorboduc and Mirror for Magistrates. Her portrait was painted by Philip de Laszlo in 1910.

Personal life, marriage and bisexuality

Vita and Rosamund Grosvenor

Vita's first real friend was Rosamund Grosvenor, who was four years her senior. Vita met Rosamund at Miss Woolf's school in 1899, when Rosamund had been invited to cheer Vita up while her father was fighting in the Boer war. Rosamund and Vita later shared a governess for their morning lessons. Vita fell in love with Rosamund, whom she called 'Roddie' or 'Rose'. Rosamund, whom Vita called 'the Rubens lady' because she was pink and white and curvy, was besotted with her. "Oh, I dare say I realized vaguely that I had no business to sleep with Rosamund, and I should certainly never have allowed anyone to find it out," she admits in the secret journal, but she saw no conflict between the two relationships: "I really was innocent." Their secret relationship ended when Vita married in 1913.

Lady Sackville invited Rosamund to visit the family at their villa in Monte Carlo; she also stayed with Vita at Knole, at Rue Lafitte and at Sluie. During the Monte Carlo visit Vita wrote in her diary " I love her so much ". When Rosamund left, Vita wrote "Strange how little I minded, she has no personality, that's why."

Marriage

In 1913, Sackville-West married Harold Nicolson, nicknamed Hadji, and the couple moved to Cospoli, Constantinople. Nicolson was at different times a diplomat, journalist, broadcaster, Member of Parliament, author of biographies and novels and also bisexual in what would now be called an open marriage. Both Sackville-West and her husband had consecutive same-sex relations, as was common among the Bloomsbury Group of writers and artists with which they had some association. These were no impediment to a true closeness between Sackville-West and Nicolson, as is seen from their nearly daily correspondence (published after their deaths by their son Nigel), and from an interview they gave for BBC radio after World War II. Nicolson gave up his diplomatic career partly so that he could live with Sackville-West in England, uninterrupted by long solitary postings to missions abroad.

They returned to England in 1914 and bought Long Barn, in Kent; they stayed from 1915 to 1930 and employed their friend the architect Edwin Lutyens to help design a small parterre. The couple had two children: Nigel, also a politician and writer, and Benedict, an art historian. In the 1930s, the family acquired and moved to Sissinghurst Castle, near Cranbrook, in Kent. Sissinghurst had once been owned by Vita's ancestors, which provided a natural dynastic attraction to her following the loss of Knole. There the couple created the renowned gardens that are now run by the National Trust.

Relationship with Violet Trefusis

The same-sex relationship that had the deepest and most lasting effect on Sackville-West's personal life was with the novelist Violet Trefusis, daughter to courtesan Alice Keppel. They first met when Sackville-West was aged twelve and Trefusis ten, and attended school together for a number of years. The relationship began while both were in their teens. Both married, but by the time both of Sackville-West's sons were no longer toddlers, she and Trefusis had eloped several times from 1918 on, mostly to France, where Sackville-West would dress as a young man when they went out. The affair eventually ended badly, with Trefusis pursuing Sackville-West to great lengths until Sackville-West's affairs with other women finally took their toll.

Also, the two women had made a bond to remain exclusive to one another, meaning that although both women were married, neither could engage in sexual relations with her own husband. Sackville-West received allegations that Trefusis had been involved sexually with her own husband, indicating she had broken their bond, prompting her to end the affair. By all accounts, Sackville-West was by that time looking for a reason, and used that as justification. Despite the poor ending, the two women were devoted to one another, and deeply in love, and continued occasional liaisons for a number of years afterward, but never rekindled the affair.

Vita's novel Challenge also bears witness to this affair: Sackville-West and Trefusis had started writing this book as a collaborative endeavour, the male character's name, Julian, being Sackville-West's nickname while passing as a man. Her mother, Lady Sackville, found the portrayal obvious enough to insist the novel not be published in England; her son Nigel (1973, p. 194), however, praises her: "She fought for the right to love, men and women, rejecting the conventions that marriage demands exclusive love, and that women should love only men, and men only women. For this she was prepared to give up everything… How could she regret that the knowledge of it should now reach the ears of a new generation, one so infinitely more compassionate than her own?"

Affair with Virginia Woolf

The affair for which Sackville-West is most remembered was with the prominent writer Virginia Woolf in the late 1920s. Woolf wrote one of her most famous novels, Orlando, described by Sackville-West's son Nigel Nicolson as "the longest and most charming love-letter in literature", as a result of this affair. Unusually, the moment of the conception of Orlando was documented: Woolf writes in her diary on 5 October 1927: "And instantly the usual exciting devices enter my mind: a biography beginning in the year 1500 and continuing to the present day, called Orlando: Vita; only with a change about from one sex to the other" (posthumous excerpt from her diary by husband Leonard Woolf).

Other affairs

Vita Sackville-West also had a passionate affair with Hilda Matheson, head of the BBC Talks Department. "Stoker" was the pet name given to Hilda by Sackville-West, during their brief affair between 1929 and 1931.

In 1931 Sackville-West became involved in an affair with journalist Evelyn Irons, who had interviewed her after The Edwardians became a bestseller.[1]

She was also involved with her sister-in-law Gwen St. Aubyn, Mary Garman and others not listed here.

Well known writings

The Edwardians (1930) and All Passion Spent (1931) are perhaps her best known novels today. In the latter, the elderly Lady Slane courageously embraces a long suppressed sense of freedom and whimsy after a lifetime of convention. This novel was faithfully dramatized by the BBC in 1986 starring Dame Wendy Hiller.

Sackville-West's science-fantasy Grand Canyon (1942) is a "cautionary tale" (as she termed it) about a Nazi invasion of an unprepared United States. The book takes an unsuspected twist, however, that makes it something more than a typical invasion yarn.

In 1946 Sackville-West was made a Companion of Honour for her services to literature. The following year she began a weekly column in The Observer called "In your Garden". In 1948 she became a founder member of the National Trust's garden committee.

She is less well known as a biographer, and the most famous of those works is her biography of Saint Joan of Arc in the work of the same name. Additionally, she composed a dual biography of Saint Teresa of Ávila and Therese of Lisieux entitled The Eagle and the Dove, a biography of the author Aphra Behn, and a biography of her own grandmother, entitled Pepita.

Legacy

Sissinghurst Castle is now owned by the National Trust, given by Sackville-West's son Nigel in order to escape payment of inheritance taxes.[2] Its gardens are famous[2] and remain the most visited in all of England.

A recording was made of Vita Sackville-West reading from her poem The Land. This was on four 78rpm sides in the Columbia Records 'International Educational Society' Lecture series, Lecture 98 (Cat. no. D 40192/3).[3]

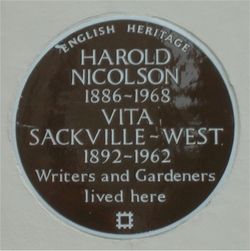

There is a brown "blue plaque" commemorating her and Harold Nicolson on their house in Ebury Street, London SW1.

Writings

Poetry

- Chatterton (1909)

- A Dancing Elf (1912)

- Constantinople: Eight Poems (1915)

- Poems of West and East (1917)

- Orchard and Vineyard (1921)

- The Land (1926)

- King's Daughter (1929)

- Sissinghurst (1931)

- Invitation to Cast out Care (1931`)

- Solitude (1938)

- The Garden (1946)

Novels

- Heritage (1919)

- The Dragon in Shallow Waters (1921)

- The Heir (1922)

- Challenge (1923)

- Grey Waters (1923)

- Seducers in Ecuador (1924)

- Passenger to Teheran (1926)

- The Edwardians (1930)

- All Passion Spent (1931)

- The Death of Noble Godavary and Gottfried Künstler (1932)

- Thirty Clocks Strike the Hour (1932)

- Family History (1932)

- The Dark Island (1934)

- Grand Canyon (1942)

- Devil at Westease (1947)

- The Easter Party (1953)

- No Signposts in the Sea (1961)

Translations

- Duineser Elegien: Elegies from the Castle of Duino, by Rainer Maria Rilke trns. V. Sackville-West (Hogarth Press, London, 1931)

Biographies/Other works

- Passenger to Teheran (Hogarth Press 1926, reprinted Tauris Parke Paperbacks 2007, ISBN 978-1-84511-343-8)

- Knole and the Sackvilles (1922)

- Saint Joan of Arc (Doubleday 1936, reprinted M. Joseph 1969)

- Pepita (Doubleday, 1937, reprinted Hogarth Press 1970)

- The Eagle and The Dove (M. Joseph 1943)

- Twelve Days: an account of a journey across the Bakhtiari Mountains of South-western Persia (M. Haag 1987, reprinted Tauris Parke Paperbacks 2009 as Twelve Days in Persia, ISBN 978-1-84511-933-1)

Notes

- ↑ Brenner, Felix (April 25, 2000). "Obituary: Evelyn Irons". The Independent (London). http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qn4158/is_20000425/ai_n14306831. Retrieved 2007-02-05.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "A happy return to manure". The Economist. 2 October 2008. http://www.economist.com/books/displaystory.cfm?story_id=12333119&fsrc=rss. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ↑ Catalogue of Columbia Records, Up to and including Supplement no. 252 (Columbia Graphophone Company, London September 1933), p. 375.

References

- Victoria Glendinning: Vita: The Life of V. Sackville-West, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1983

- Nigel Nicolson and Vita Sackville-West: Portrait of a Marriage, The University of Chicago Press, 1998. First published 1973. ISBN 0-226-58357-0

- Michael Carney, Stoker: The Life of Hilda Matheson, privately published, Llangynog, 1999

Further reading

- David Cannadine: Portrait of More Than a Marriage: Harold Nicolson and Vita Sackville-West Revisited. From Aspects of Aristocracy, pp. 210–42. (Yale University Press, 1994) ISBN 0-300-05981-7

- Robert Cross and Ann Ravenscroft-Hulme: Vita Sackville-West: A Bibliography (Oak Knoll Press, 1999) ISBN 1-58456-004-5

- Victoria Glendinning: Vita: The Life of V. Sackville-West (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1983)

- Nigel Nicolson and Vita Sackville-West: Portrait of a Marriage. (The University of Chicago Press, 1998. First published 1973) ISBN 0-226-58357-0

- Peggy Wolf: Sternenlieder und Grabgesänge. Vita Sackville-West: Eine kommentierte Bibliographie der deutschsprachigen Veröffentlichungen von ihr und über sie 1930 - 2005. (Daphne-Verlag, Göttingen, 2006) ISBN 3-89137-041-5

External links

- Fuller list of Vita Sackville-West's publications

- Vita Sackville-West as a garden designer

- Portrait photos at npg.org.uk [1] [2]

- Vita Sackville-West reads from her poem The Land [3]

- Archival material relating to Vita Sackville-West listed at the UK National Register of Archives